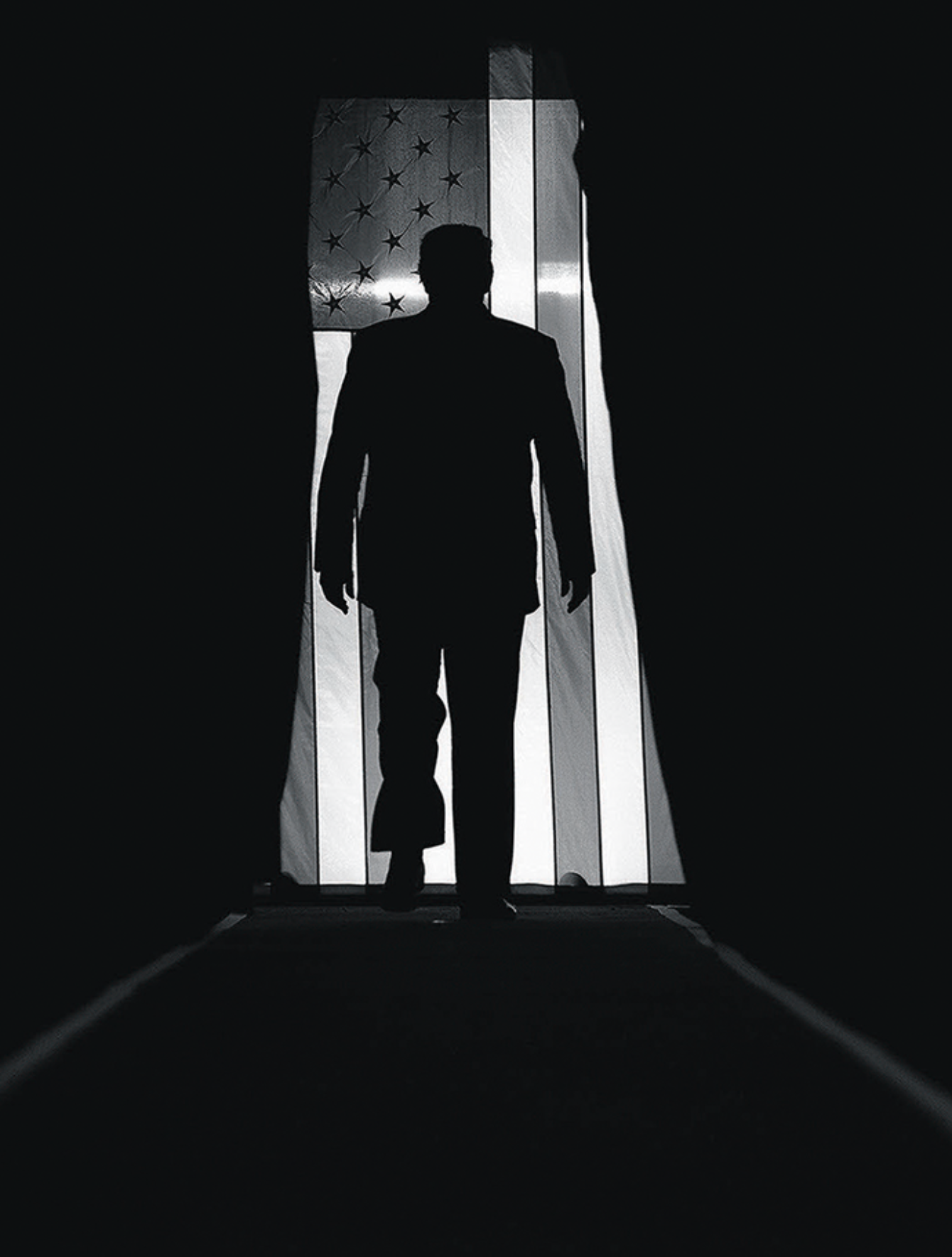

In our so-called Trump Era, freedom and power aren’t what they used to be. Both are undergoing radical conceptual transformations. Marshall assumed a mutual compatibility between the two. No such assumption can be made today.

Although the strategy of accruing overwhelming military might to advance the cause of liberty persisted throughout the period misleadingly enshrined as the Cold War, it did so in attenuated form. The size and capabilities of the Red Army, exaggerated by both Washington and the Kremlin, along with the danger of nuclear Armageddon, by no means exaggerated, suggested the need for the United States to exercise a modicum of restraint. Even so, Marshall’s pithy statement of intent more accurately represented the overarching intent of U.S. policy from the late 1940s through the 1980s than any number of presidential pronouncements or government-issued manifestos. Even in a divided world, policymakers continued to nurse hopes that the United States could embody freedom while wielding unparalleled power, admitting to no contradictions between the two.

With the end of the Cold War, Marshall’s axiom came roaring back in full force. In Washington, many concluded that it was time to pull out the stops. Writing in Foreign Affairs in 1992, General Colin Powell, arguably the nation’s most highly respected soldier since Marshall, anointed America “the sole superpower” and, quoting Lincoln, “the last best hope of earth.” Civilian officials went further, designating the United States as history’s “indispensable nation.” Supposedly uniquely positioned to glimpse the future, America took it upon itself to bring that future into being, using whatever means it deemed necessary. During the ensuing decade, U.S. troops were called upon to make good on such claims in the Persian Gulf, the Balkans, and East Africa, among other venues. Indispensability imposed obligations, which for the moment at least seemed tolerable.

After 9/11, this post–Cold War posturing reached its apotheosis. Exactly sixty years after Marshall’s West Point address, President George W. Bush took his own turn in speaking to a class of graduating cadets. With splendid symmetry, Bush echoed and expanded on Marshall’s doctrine, declaring, “Wherever we carry it, the American flag will stand not only for our power, but for freedom.” Yet something essential had changed. No longer content merely to defend against threats to freedom—America’s advertised purpose in World War II and during the Cold War—the United States was now going on the offensive. “In the world we have entered,” Bush declared, “the only path to safety is the path of action. And this nation will act.” The president thereby embraced a policy of preventive war, as the Japanese and Germans had, and for which they landed in the dock following World War II. It was, in effect, Marshall’s injunction on steroids.

We are today in a position to assess the results of following this “path of action.” Since 2001, the United States has spent approximately $6.5 trillion on several wars, while sustaining some sixty thousand casualties. Post-9/11 interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere have also contributed directly or indirectly to an estimated 750,000 “other” deaths. During this same period, attempts to export American values triggered a pronounced backlash, especially among Muslims abroad. Clinging to Marshall’s formula as a basis for policy has allowed the global balance of power to shift in ways unfavorable to the United States.

At the same time, Americans no longer agree among themselves on what freedom requires, excludes, or prohibits. When Marshall spoke at West Point back in 1942, freedom had a fixed definition. The year before, President Franklin Roosevelt had provided that definition when he described “four essential human freedoms”: freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. That was it. Freedom did not include equality or individual empowerment or radical autonomy.

As Army chief of staff, Marshall had focused on winning the war, not upending the social and cultural status quo (hence his acceptance of a Jim Crow army). The immediate objective was to defeat Nazi Germany and Japan, not to subvert the white patriarchy, endorse sexual revolutions, or promote diversity.

Further complicating this ever-expanding freedom agenda is another factor just now beginning to intrude into American politics: whether it is possible to preserve the habits of consumption, hypermobility, and self-indulgence that most Americans see as essential to daily existence while simultaneously tackling the threat posed by human-induced climate change. For Americans, freedom always carries with it expectations of more. It did in 1942, and it still does today. Whether more can be reconciled with the preservation of the planet is a looming question with immense implications.

When Marshall headed the U.S. Army, he was oblivious to such concerns in ways that his latter-day successors atop the U.S. military hierarchy cannot afford to be. National security and the well-being of the planet have become inextricably intertwined. In 2010, Admiral Michael Mullen, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, declared that the national debt, the prime expression of American profligacy, had become “the most significant threat to our national security.” In 2017, General Paul Selva, Joint Chiefs vice chair, stated bluntly that “the dynamics that are happening in our climate will drive uncertainty and will drive conflict.”

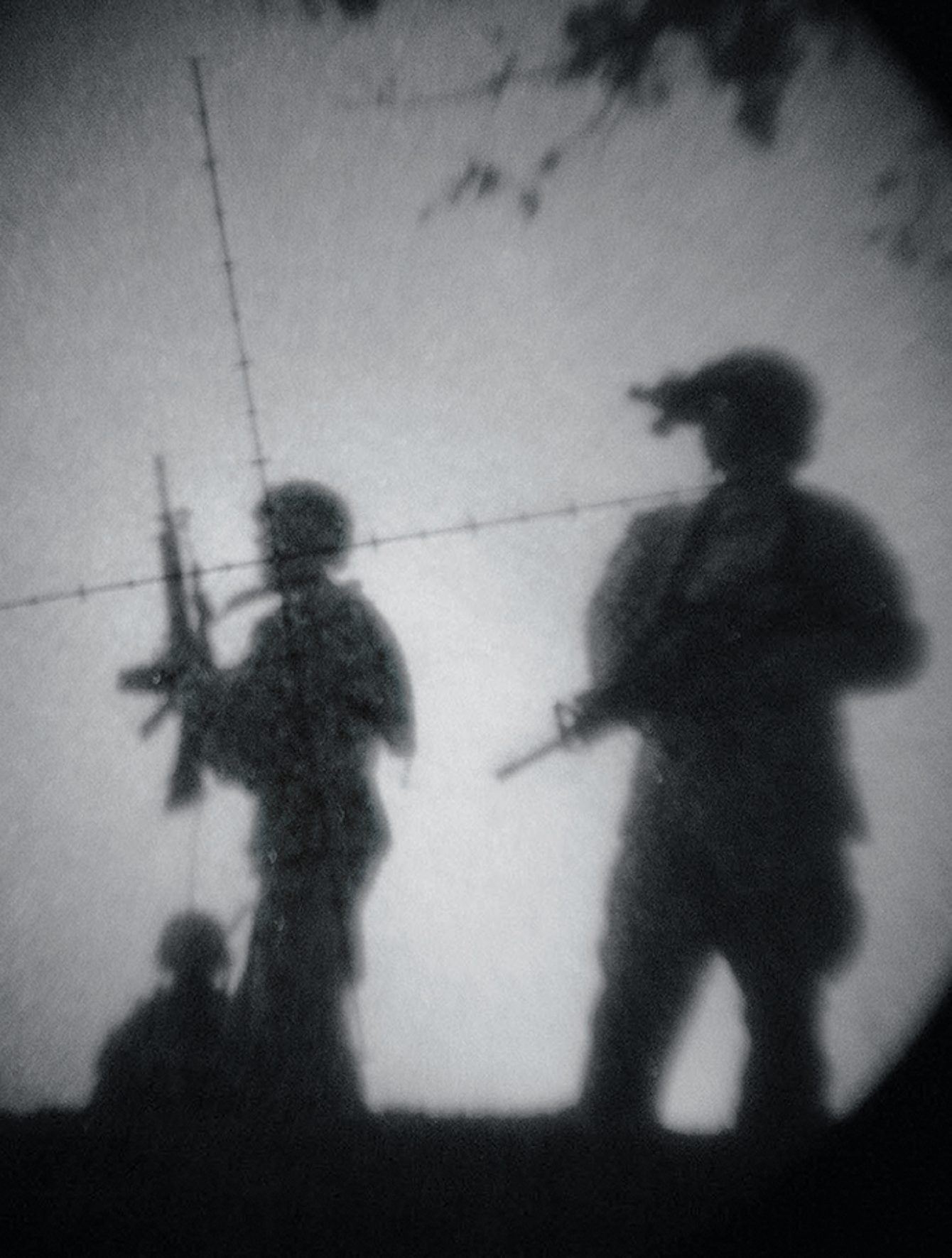

As for translating objectives into outcomes, Marshall’s “great citizen-army” is long gone, probably for good. The tradition of the citizen-soldier that Marshall considered the foundation of the American military collapsed as a consequence of the Vietnam War. Today the Pentagon relies instead on a relatively small number of overworked regulars reinforced by paid mercenaries, aka contractors. The so-called all-volunteer force (AVF) is volunteer only in the sense that the National Football League is. Terminate the bonuses that the Pentagon offers to induce high school graduates to enlist and serving soldiers to re-up, and the AVF would vanish.

Furthermore, the tasks assigned to these soldiers go well beyond simply forcing our adversaries to submit, which was what we asked of soldiers in World War II. Since 9/11, those tasks include something akin to conversion: bringing our adversaries to embrace our own conception of what freedom entails, endorse liberal democracy, and respect women’s rights. Yet to judge by recent wars in Iraq (originally styled Operation Iraqi Freedom) and Afghanistan (for years called Operation Enduring Freedom), U.S. forces are not equipped to accomplish such demanding work.

Leave a comment