TGIF: On the Pursuit of Happiness

Posted by M. C. on July 5, 2024

The equation, however, is invidious. It suggests that other people necessarily are impediments to one’s happiness and thus one should sacrifice one’s happiness at least to some extent. But why would anyone believe that “selfishness”—making the most of one’s life by holding it as one’s ultimate value—entails the disvaluing of other people? It’s crazy on its face. Rand, like the ancient Greeks, understood that he who cares about only himself demonstrates that he doesn’t care enough.

https://libertarianinstitute.org/articles/tgif-pursuit-happiness/

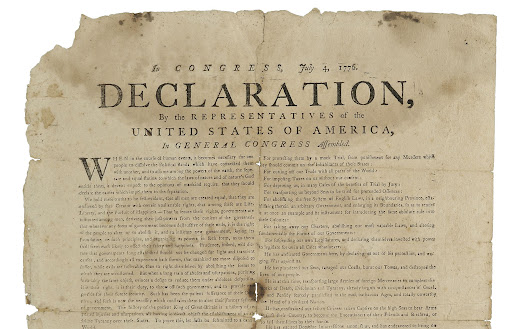

The most remarkable phrase in the Declaration of Independence, whose anniversary we just celebrated, is the pursuit of happiness. Looking back 248 years, that phrase may strike the modern ear as strange for a political document. But it apparently did not seem that way to Americans in 1776. The second paragraph told the world:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

The term among these indicates that Thomas Jefferson and the Second Continental Congress did not think that life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness were our only unalienable rights. But the pursuit of happiness made the brief enumeration, which speaks volumes.

The first thing to note is that Jefferson did not write that we had a right to happiness, but only the right to pursue it. Legal scholar and historian Carli N. Conklin of the University of Missouri School of Law states in “The Origin of the Pursuit of Happiness”:

[T]he pursuit of happiness is not a legal guarantee that one will obtain happiness, even when happiness is defined within its eighteenth-century context. It is instead, an articulation of the idea that as humans we were created to live, at liberty, with the unalienable right to engage in the pursuit.

Through historical investigation, Conklin shows that contrary to common belief, the phrase was no “glittering generality” (in Carl Becker’s phrase) back them but rather was a term of substance.

I trust no one will take seriously that the omission of property from the list of examples means that Jefferson et al. thought property unimportant. Of course, it did not mean that. We know that the people behind the Declaration understood the deep importance of private property to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. A possible reason for not listing it is that property was often used differently from the way we use it today. While we say, “That’s my property,” an 18th-century person might say, “I have a property in that,” although today’s usage was hardly unknown back then. James Madison, who was not a member of the Continental Congress but who had a lot of say about property, used the word both ways. However, here are examples of what he called “the larger and juster meaning” of the word:

[A] man has a property in his opinions and the free communication of them. [Emphasis added.]

He has a property of peculiar value in his religious opinions, and in the profession and practice dictated by them.

He has a property very dear to him in the safety and liberty of his person.

He has an equal property in the free use of his faculties and free choice of the objects on which to employ them. [Emphasis added.]

In a word, as a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights.

It’s widely known that Jefferson and other founders were deeply influenced by John Locke,

Be seeing you

Leave a comment