Of course, apart from world encompassing imperialist frameworks and Russophobia, the British also introduced their American counterparts to the central banking and government propaganda apparatuses necessary to expanding Washington’s cheaply won contiguous land empire of the nineteenth century abroad in the twentieth. Having adopted these methods, Washington could, when Britain’s strength was finally exhausted, “Pick up the torch of empire from our [Britain’s] still cooling fingers.”8

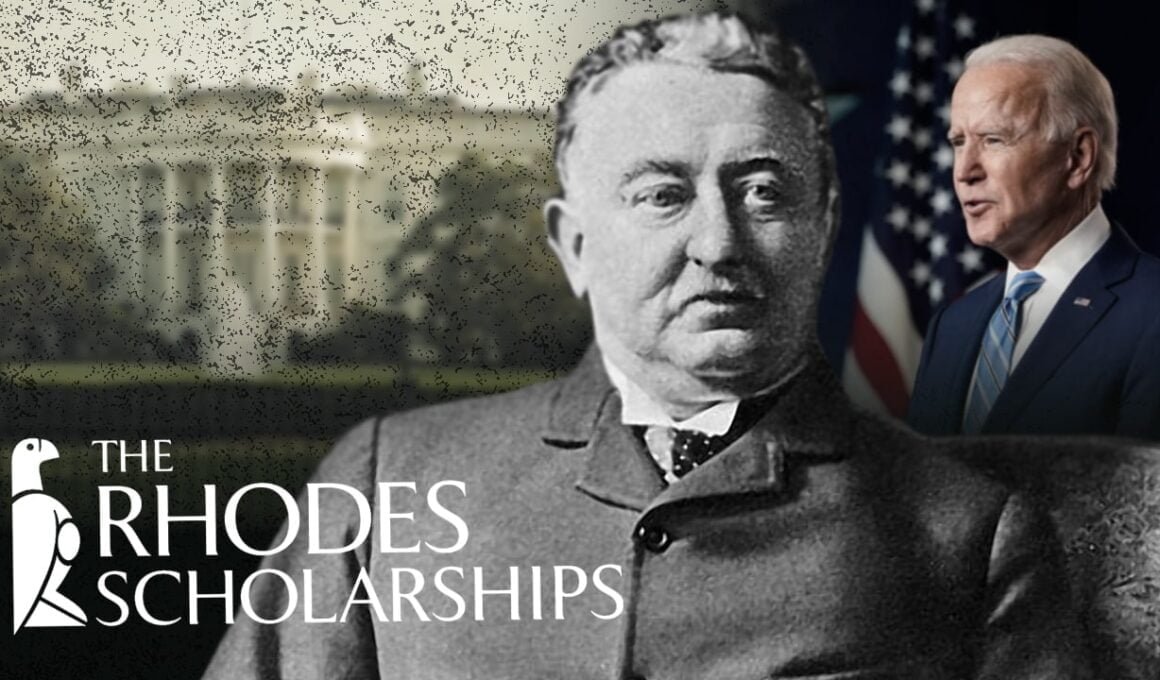

In 1877, before he had made his fortune via the founding of De Beers Consolidated Mines and the British South Africa Company, the imperialist par excellence Cecil Rhodes had dictated a part of his will thusly: “[To make provision] for the establishment, promotion and development of a Secret Society, the true aim and object whereof shall be for the extension of British rule throughout the world.” This was to include, “The ultimate recovery of the United States of America.”1

This grandiose vision was pragmatically tempered in the final version of his will (1902), which instead set up an eponymous scholarship, the stated intention of which was to, “promote unity among English speaking nations.” Thus was the Rhodes Scholarship, which sees a handful of America’s future leaders shipped off to Oxford each year, conceived of and brought into being.2

Just looking over a list of some of those selected, the influence of British thinking on American grand strategy in the century that followed becomes all too explicable: From Stanley Hornbeck, special advisor to FDR’s Secretary of State Cordell Hull, the longest serving Secretary of State in U.S. history, to J. William Fullbright, senator and longest tenured Chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee (1945-1974), to JFK and LBJ’s Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and Walt Rostow, LBJ’s National Security Advisor: these men were among the most influential hands steering U.S. foreign policy from the 1930s onward.

Later architects of U.S. policy to pass through Oxford via the program include Richard Haas, President of the Council on Foreign Relations and Director of Policy Planning for George W. Bush (2001-2003), Joseph Nye, chair of the National Intelligence Council and Deputy Secretary of Defense under Bill Clinton3 (1993-1995), Strobe Talbot, Deputy Secretary of State and lead architect of Clinton’s Russia and NATO expansion policies (1994-2001), Susan Rice, Barack Obama’s National Security Advisor (2013-2017), Ash Carter, Secretary of Defense under Obama (2015-2017), and arguably the worst U.S. Ambassador to Russia ever, Michael McFaul (2012-2014).

As an aside, given the catastrophic performance of these later figures it is worth noting that apart from absorbing British principles of imperial strategy—the work of the Oxonian Halford Mackinder (1861-1947) clearly having influenced that of the foundational American realist Nicholas Spykman (1893-1943), who in turn greatly influenced John Foster Dulles (Dwight Eisenhower’s Secretary of State from 1953-1959)—American policy architects seem to have also imbibed the abiding British suspicion of the Russians, as well as their tactics for dealing with the “barbarians,” as the aforementioned ex-Ambassador McFaul described them on Twitter a week ago.

Be seeing you