https://libertarianinstitute.org/articles/tgif-thinking-save-lives/

The Cambridge economist Joan Robinson (1903-1983) wisely said, “The purpose of studying economics is not to acquire a set of readymade answers to economic questions, but to learn how to avoid being deceived by economists.”

Excellent point, though I would both broaden and narrow her category of suspects. I would include most politicians, bureaucrats, pundits, and social-science and humanities professors in the suspect group. And I would exclude the economists — spoiler alert: primarily those of the Austrian school, although others stand out — who paint a much more realistic picture of the world than the others do.

For the record, Robinson was sympathetic to John Maynard Keynes and, later in life, communist China’s Mao Zedong, and North Korea’s Kim Il Sung. Obviously, her study of economics did not teach her how to avoid being deceived by all who represented themselves as economists. (I heard once that Che Guevera became head of Cuba’s national bank in 1959 because when Fidel Castro asked his cadre, “Who here is a good economist?” Guevara, thinking he heard, “Who here is a good communist?” raised his hand. But that’s apparently apocryphal.)

At any rate, mankind would have been spared a good deal of misery had people learned at an early age to engage in the economic way of thinking. If I were to sum it up in a short phrase, I would say: in a world in which the law of identity, causality, and scarcity rule, you can’t do just one thing. Human action has consequences. This apparently is also the first law of ecology, but oddly, environmentalists (as opposed to humanists) seem ignorant of it.

The point is that all human action has rippling consequences across society and across time. The economist who called his textbook The Economic Way of Thinking, the late Paul Heyne, wrote, “All social phenomena emerge from the choices of individuals in response to expected benefits and costs to themselves.” (Happily, Peter J. Boettke and David L. Prychitko keep updating the book. It’s in its 10th edition.)

Heyne’s maxim applies to the choices of politicians and bureaucrats also. So before proposing or endorsing a government policy, one ought to wonder about the social phenomena that are likely to emerge from it. Economics is an indispensable tool in this respect.

Henry Hazlitt’s classic, Economics in One Less, is a great way to get started. Hazlitt wrote, “The art of economics consists in looking not merely at the immediate but at the longer effects of any act or policy; it consists in tracing the consequences of that policy not merely for one group but for all groups.” Hazlitt’s book elaborated an important message of his intellectual ancestor, Frédéric Bastiat, the 19th-century French laissez-faire liberal, in the classic essay “That Which Is Seen and That Which Is Unseen.”

Individuals who adopt this way of thinking are better equipped to judge the promises of politicians, etc. who support taxes, minimum-wage laws, rent control, general wage-and-price controls, and the rest of the program of political authority over contractual freedom and other peaceful conduct. Even well-intended regulations will have unintended bad secondary consequences. Good intentions are never enough.

Any good introduction to the economic way of thinking will introduce readers to concepts like opportunity cost, the unseen, sunk costs, the margin, and tradeoffs. Most people seem to intuit some of these in their own lives. But they fail to do so when it comes to society as a whole. They are encouraged by politicians and pundits to think that common sense in private life does not apply to the big picture.

Opportunity cost refers to the fact when you choose a course of action, you necessarily foreclose another course of action. The true cost, then, is the (subjectively judged) next-best choice forgone. If you buy something for two dollars, your cost isn’t really two dollars. It’s what you regard as the next best use of those two dollars — the future not chosen. You might decide afterward that you made a mistake: “I could’ve had a V-8!” Good economists do not regard people as omniscient robots.

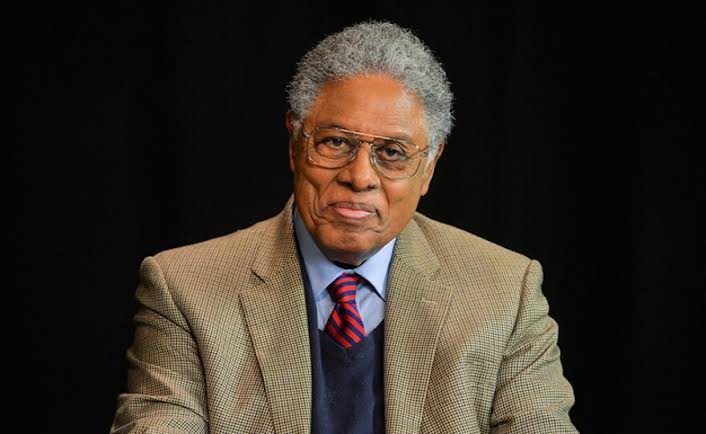

Opportunity cost is another way of looking at trade-offs. If you do or choose A you can’t do or choose B. Thus you trade B for A. Trade-offs are inescapable. Thomas Sowell, for whom the word genius is woefully inadequate, dramatically drew attention to this feature of life when he wrote, “There are no solutions. There are only trade-offs.” Today’s problems, he adds, may well be the result of yesterday’s solutions. We’d do well to bear this in mind, especially in deciding what the government should be doing (if anything).

Be seeing you