Four years of preventable and utterly pointless bloodshed ensued. Thanks to calls to oppose aggression and defend allies, what should have been a regional war in the Balkans became a major Europe-wide war. Even worse, with the Treaty of Versailles and the inclusion of the absurd “War Guilt” clause against Germany, the war set the stage for the far more destructive Second World War.

by Ryan McMaken

With proponents of military intervention and war, it’s always 1938, and every attempt to substitute diplomacy for escalation and war is “appeasement.”

Last week, for example, Ukrainian legislator Lesia Vasylenko accused Western leaders of appeasement over Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine, stating “This is the same as 1938 when also the world and the United States in particular were averting their eyes from what was being done by Hitler and his Nazi Party.” The week before that, Estonian legislator Marko Mihkelson declared “I hope I’m wrong but I smell ‘Munich’ here. ”

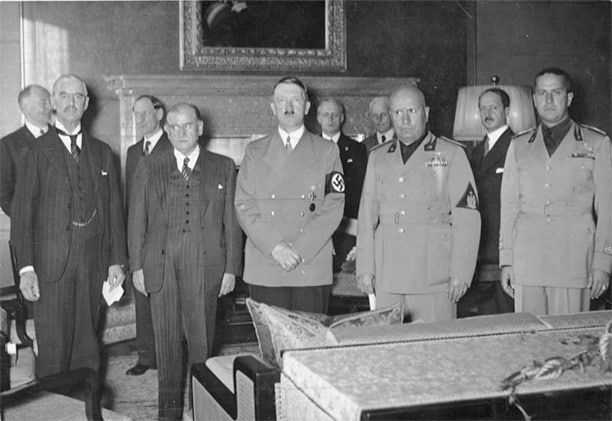

These, of course, are references to the notorious Munich conference of 1938 when UK PM Neville Chamberlain (and others) agreed to allow Hitler’s Germany to annex the Sudetenland in Czechoslovakia as a means to avoid a general war in Europe. The “appeasement,” of course, failed to prevent war because Hitler’s regime actually planned to annex much more than that.

Ever since, the “Lesson of Munich” for advocates of military intervention is that it’s always best to escalate international conflicts and meet all perceived aggressors with immediate military force rather than embrace compromise or non-intervention.

Americans have made similar references with pundits from Larry Elder to Peter Singer peppering their musings on the Ukraine War with the Munich analogy. One need only enter “Munich” and “1938” into a Twitter search to receive an apparently endless number of tweets from newly minted American foreign policy experts about how anything less than World War III is Munich all over again. Historically, countless American politicians have used the analogy as well. 1980s Cold Warriors denounced Ronald Reagan’s efforts to limit nuclear weapons as Munich-style appeasement. Republicans routinely claimed Obama’s Iran diplomacy was the same.

But it is not, in fact, the case that every act of diplomacy or compromise designed to avoid war is appeasement. Moreover, we can find countless examples in which non-intervention and a refusal to escalate a situation was—or would have been—the better choice.

In other words, it’s not always 1938. Rather than fixating on the “Lesson of 1938” the better lesson to learn is often the “Lesson or 1914” or perhaps even the lessons of 1853, 1956, or 1968. In all these cases, military escalation was—or would have been—the wrong response. Moreover, in the age of nuclear weapons—something that did not exist in 1938—the world is a different place and confrontation with a nuclear power could potentially bring about the end of human civilization. Casually bandying about demands for a “no fly zone”—which would mean war with Russia—is both irresponsible and the sort of rhetoric fit for a non-nuclear world that ceased to exist many decades ago.

The Foundations of the “Lessons of Munich”

The supposed Lesson of Munich is based on two basic pillars. The first is the assumption that any act of military aggression will lead to many more acts of military aggression if not forcefully countered. It is basically a variation on the domino theory: if one nation submits to conquest by an aggressive neighbor, other nations will soon be forced to submit as well. This assumes every allegedly aggressive state has the same motivations as Nazi Germany and can plausibly seek a large, region-wide chain of military conquests across numerous states.

The second pillar of the Lesson of Munich is that, since every aggressive military act is likely to lead to many more, the only realistic option is to meet aggression with escalation, and a no-compromise response.

This is precisely why Western advocates of military adventurism repeatedly equate Hitler with every foreign leader Western elites don’t like. Or, as noted at The Conversation:

This kind of parallelism is not new; it is used every time there is a new enemy the public opinion should focus on. In recent years, according to Western rhetoric, Adolf Hitler has already been apparently reincarnated several times – as Saddam Hussein, Mohammad Qaddafi, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and more besides.

In 2022, Putin is the new Hitler, which necessarily means to some that any failure to respond to the Russian invasion with a full-blown military response from the West is a Munich-style appeasement.

The fact that the events of 1938 are so well known by so many has helped considerably in pushing the narrative that compromise or non-intervention is appeasement. For most Americans, it’s likely the only event in the history of diplomacy they actually know anything about. Never mind the fact that the Lesson of Munich has often been proven quite inapplicable to the modern world. As noted by Robert Kelly at the hardly non-interventionist publication 1945:

This frightening image of falling dominoes is not actually historically common though, thankfully. It was in the 1930s, but it was not, for example, in the Cold War. Aggressors do not always read one victory in place to mean they can automatically push on other ‘dominoes.’ Deterrence is structured by local and historical factors; some commitments are much more credible than others. So even though the US lost in Vietnam, North Korea or East Germany did not attack South Korea or West Germany, just as the US did not attack Cuba or Nicaragua after the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan.

In Ukraine that means that Western reticence to fight directly against the Russians in Ukraine does not automatically mean that Putin will test NATO’s collective security commitment or that China will attack Taiwan.

But none of this matters when the public believes what its told by politicians and the media about how every rogue state is the equivalent of Nazi Germany. There is no foreign-policy lesson to learn except that of opposing each new “Hitler.”

The Lesson of 1914

Yet, there are other competing lessons to be learned. Lessons can be found, say, with the lead up to the Crimean War in 1853 or the July Crisis of 1914. (Ask the average American about either of these and you will probably receive a blank stare.)

In both of these cases, regimes claimed they were countering aggression by foreign states and protecting either “allies” or oppressed minorities in the lands being subjected to conquest.

The lead up the First World War provides an especially cautionary tale in which the major powers rushed to intervene in the name of supporting allies. The Austrian regime issued an ultimatum to the Serbians, and the Russians—with the support of France, Europe’s biggest democracy—mobilized in support of traditional ally Serbia. The Germans then mobilized in support of Austria-Hungary. Later, the regimes in the United Kingdom and the United States employed propaganda about alleged German war crimes in Belgium to ensure their respective countries entered the war. British politicians also claimed they must intervene to assist Britain’s Entente allies in resisting aggression. Four years of preventable and utterly pointless bloodshed ensued. Thanks to calls to oppose aggression and defend allies, what should have been a regional war in the Balkans became a major Europe-wide war. Even worse, with the Treaty of Versailles and the inclusion of the absurd “War Guilt” clause against Germany, the war set the stage for the far more destructive Second World War.

Yet, the war was a result of regimes doing—from their own perspectives—what the “Lesson of Munich” dictates: rush to war and immediately escalate and confront “enemies” with military force in the name of countering aggression.

The Lesson of 1914 is certainly instructive today. Escalation is extraordinarily unwise, especially if there is the potential of turning limited wars into mega-scale disasters. Moreover, in the case of the United States, the complexity of the war’s causes meant there was no justifiable reason at all for the United States to enter. There was no “good guy” in the war and American participation only further extended the bloodshed.

Fortunately, in spite of its pretensions of being the global guarantor of freedom always and everywhere, the United States has, at least twice, behaved as if it has learned the Lesson of 1914. The first was in 1956 when Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary when the Hungarian regime—an ostensibly sovereign state—became too uppity to suit Moscow. So, Soviet military might moved in to ensure Hungary remained sufficiently under Moscow’s control. Thousands of Hungarians were killed. Did NATO mobilize against this aggression? Did Eisenhower ready America’s bombers? No.

Then, in Prague in 1968, Czechoslovakian resistance to Moscow led to an invasion of 200,000 foreign troops and 2,500 tanks from the pro-Soviet regimes of the Warsaw Pact. Again, the United States took no action.

This, of course, was the right decision on the part of the U.S. and NATO. Heeding the Lesson of Munich, on the other hand, would have meant direct confrontation between NATO and the Soviet Union—a de facto confrontation between the United States and the USSR. This would have greatly increased the likelihood of global nuclear war.

Naturally, some anti-Soviet activists cried “appeasement!” at the time. Fortunately, they were ignored. A curious difference between 1956 and now, however, is that at the time most of the critics of American inaction were on the anti-Soviet Right. Today, it is the Left where we mostly find those howling about Munich and blithely pushing for a U.S.-Russia war while downplaying the risk of a nuclear apocalypse. But those who are now demanding for World War III are a cautionary example of what happens when we obsess over the Lesson of 1938 and ignore the Lesson of 1914.

This article was originally featured at the Ludwig von Mises Institute

Be seeing you